22nd July 2025

Key takeaways

- Banking supervision’s ability to be effective is being challenged by several long-term, irreversible trends.

- To adapt, supervision needs to “10x” and overcome key obstacles like high labor intensity, over-specialization, and fear of making mistakes.

- This essay proposes a 10x roadmap focused on: agility and prioritization, differentiated intensity of supervisory activities, and autonomy and alignment.

- Cybernetic and superintelligent supervision is achievable but requires adoption of the right technology (digital/AI), mindset (learning), and culture (agile).

First Principles

At its core, banking supervision is a feedback mechanism. Without it, banks and the banking system would veer frequently into crisis, imposing undue negative externalities on society.

Effective supervision provides banks with accurate and timely feedback with regards to unsafe and unsound conditions and practices. Supervisors carry this out by conducting examinations, issuing findings, and taking enforcement actions, among other means.

Ineffective supervision occurs when unsafe and unsound conditions or practices are not identified or escalated in a timely manner, or when adequate conditions or practices are falsely identified as unsafe and unsound.

Challenging trends

Supervision is under pressure from four long-term, irreversible trends.

1) The number, size, and complexity of large banks continues to grow, far outpacing the growth of supervisory teams.

2) Banking is no longer done by just banks. Technological innovation and adoption are blurring the lines between banks and nonbanks, increasing the complexity and risk surface of banking.

3) Change is happening much faster and at a compounding rate, making it difficult to keep up. See payments, AI, and crypto.

4) Supervision has less and less room for error. Public and political scrutiny of supervision continues to increase, from all sides.

For supervision to remain effective in the face of these trends, supervision must cover more, faster, and better. Incremental improvements will not suffice given the pace and interactive effects of these trends. In techspeak, supervisors must “10x” – and they must do so in the face of headcount reductions, fading memories of financial crises, and political calls to prioritize competitiveness.

In order to “10x”, supervision must overcome three key obstacles:

i) the high labor-intensity of supervisory activities like risk identification, supervisory planning, and examinations,

ii) the tendency of the workforce to over-specialize, which hardens organizational silos, and

iii) the fear of making mistakes, leading to greater reliance on checklists and negative feedback loops.

A '10x' Roadmap

Supervision can overcome these obstacles and achieve 10x performance by focusing on three key areas: (1) agility and prioritization, (2) differentiated intensity of supervisory activities, and (3) autonomy and alignment.

- Agility and Prioritization

Traditionally, supervisors have not had to be agile because banking did not change much. Deep expertise in relevant areas, e.g., credit, was highly valued. The specialization of supervisory resources was efficient, and that efficiency enabled effectiveness.

In highly dynamic environments, however, agility is more important to supervisory effectiveness than efficiency. Over-specialization becomes a liability, as it locks in resources, perspectives, and priorities when they need to be free to adapt to changing circumstances.

The philosopher Isaiah Berlin once famously noted that there are two types of people: hedgehogs and foxes. Hedgehogs know one thing really well, while foxes know many things. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella describes it as the difference between “know it all’s” and “learn it all’s”. In dynamic environments, the ability to learn and adapt is most valuable.

The graphic below shows the shift from fixed teams of specialists to a mix of hedgehogs and foxes which is needed to ensure that supervision can be agile enough to keep up in today’s dynamic environment.

Traditionally, supervisory planning and prioritization has been an annual, manual, and bureaucratic process. Inertia plays a big role, with most priorities carried over from last cycle’s priorities, with perhaps an addition and subtraction here or there. Specialists and subject matter experts – by risk stripe and by bank – exert influence via consensus building. The process is analog and linear, i.e., with analyses done by fixed teams, filtering and synthesis done by sub-committees, and prioritization done by committee level winnowing. This process has worked reasonably well because banking for a long time did not change all that much.

In a complex, rapidly changing environment, however, prioritization needs to be agile, cybernetic and dynamic to be effective. It must be continuous, not annual. There needs to be a bias for discovery – finding out what’s changing – rather than simply leveraging what was done previously. Synthesis needs to be driven by exploration and debate, rather than consensus building, because no one person or team can know everything. The process needs to be iterative and cybernetic, rather than linear, drawing from a wide range of sources, and keenly aware of feedback loops.

In short, supervisory prioritization needs to be shift from operating like a Differential Analyzer (left photo of the first analog computer, which operated through a large set of interlocking gears) and more like the neurons of a brain (right graphic).

- Differentiated intensity of supervisory activities

Examinations are the core supervisory activity. Nearly all supervisory assessments – and, by extension, nearly all supervisory feedback to banks – derive from examinations.

Examinations are highly labor intensive. They are executed by teams of up to a dozen. They can take six to twelve weeks to complete. They involve information requests to banks, iteration on what’s provided and what it means, and follow-up. Examiners must support their assessments with analyses and documentation, which means lots of drafting and re-drafting of reports.

Examinations are highly structured. This facilitates discipline, consistency, and quality control. It is hard to cut corners on an exam. That is by design.

In dynamic environments, however, the high labor intensity and rigid structure of examinations are impediments to effective supervision. They limit the ability of supervisors to modulate and approach smaller issues with less intensity than bigger issues.

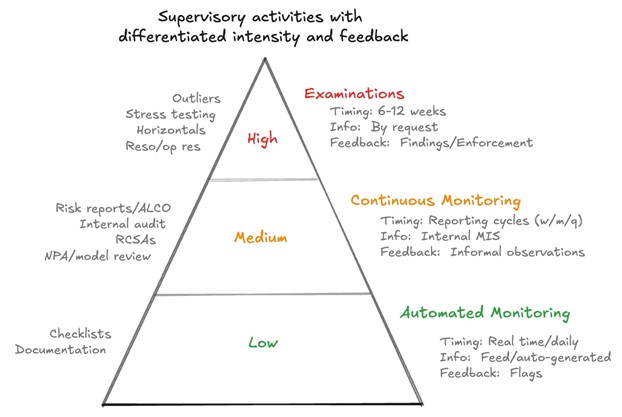

In a complex, rapidly changing world with more large banks and greater nonbank dependencies, supervisors need a wider range of tools in toolkit, not just one examination hammer. The graphic below depicts three levels: low intensity Automated Monitoring (AM) for checklist items and documentation requirements, medium intensity Continuous Monitoring (CM) based on bank risk reporting, internal audit activities, etc., and high intensity Examinations for higher risk issues, like outliers, stress testing, horizontals, etc.

- Autonomy and Alignment

Traditionally, supervisory teams were organized by bank, and each team had significant autonomy in making its assessments and providing feedback.

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis revealed significant shortcomings in this approach. Autonomy meant inconsistency, with teams taking different approaches, applying different standards, and many believing their bank to be above average.

In response, agencies like the Federal Reserve and ECB SSM reorganized their supervision teams and processes to prioritize consistency and alignment across teams. This meant the creation of numerous committees and the standardization of a wide range of processes and outputs. While this was effective in enforcing alignment, it came at the expense of autonomy and speed.

As shown in the graphic below, for supervision to be effective, supervisory teams must be highly aligned and have a high degree of autonomy to adapt to the complexities and nuances of a dynamic environment.1

Cybernetic and Superintelligent Supervision

The term cybernetic was coined by Norbert Weiner, one of the fathers of the computer. He described it as “the science of control and communication, in the animal and the machine” and emphasized the critical importance of feedback loops in guiding behavior and outcomes. A colleague later would sum it up as “the art of steermanship”.

Supervision’s effectiveness rests on its ability to steer banks to safety and soundness. In this sense, supervision has always been cybernetic. What differentiates it today, however, is the speed of change and role of technology as an accelerant of dynamism and as a tool that will enable supervision to adapt and succeed.

The increasing complexity of banking (including interlinkages with nonbanks) means supervision must also become superintelligent to be effective. Supervisors have access to more information about the banking system than any other group. This enables them to become superintelligent, provided they adopt the technology (digital/AI), mindset (learning), and culture (agility) to do so.

In future essays, I will flesh out some of the practical steps and options for moving in the direction laid out in the Roadmap presented here. Notably, technological advances, especially AI, are creating possibilities that were previously unimaginable.

In the meantime, I invite feedback, criticism, and suggestions on the ideas presented and look forward to engaging with those all of those interested in improving supervision.

Endnotes:

1. This is informed, in part, by the successful growth strategies and approaches of Netflix and Spotify. See “Netflix Freedom and Responsibility Culture Presentation” and “Spotify Engineering Culture-Part 1”.

Michael J. Hsu served as Acting Comptroller of the Currency from May 2021 to February 2025. As Acting Comptroller, Mike was the administrator of the federal banking system and chief executive officer of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. During that time he also served as a Director of the FDIC, a member of the Financial Stability Oversight Council, and chair of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council.

Prior to that, Mike led the GSIB supervision program at the Federal Reserve. He also prudentially supervised the large independent investment banks while at the Securities and Exchange Commission. During the Global Financial Crisis, he worked at the Treasury Department, followed by a stint at the IMF.

Currently, Michael is a fellow at the Aspen Institute, member of the Bretton Woods Committee, and advisor to central banks, companies, and non-profits. He collaborates with a range of stakeholders on facilitating responsible AI adoption by regulators and financial institutions.